Earlier this week, ACLU-NJ, the ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project, and the Seton Hall Law School Center for Social Justice filed a lawsuit on behalf of El Comité de Apoyo a los Trabajadores Agrícolas (CATA) – a grassroots organization advocating to improve the working and living conditions of farmworkers and the Latine immigrant community. The lawsuit argues that the exclusions in New Jersey’s wage and hour laws denying farmworkers equal wages and overtime protection are discriminatory, and that these exclusions violate the state constitution's prohibition on special laws.

ACLU-NJ Staff Attorney Molly Linhorst sat down with Edgar Aquino-Huerta, Farmworker Organizer at CATA, to talk more about his work as a farmworker, a filmmaker, a storyteller, and an advocate. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Molly Linhorst: You have deep personal experience as a farmworker. Can you tell us more about who you are and how you became involved in this line of work?

Edgar Aquino-Huerta: I was born in Puebla, Mexico. My grandfather was actually a farmer in Puebla. He had plots of sugar cane and was one of the well-known farmers of our town, so “huerta” was already in my blood and is my last name as well. "Huerta” is a form of another Spanish word, “huerto,” meaning “field” in English.

I was two years old when my mom and I came here in search of opportunities, and we came directly to South Jersey because my grandfather had established himself here years prior as a migrant worker.

Growing up in the community with many farmworkers, like my parents, I witnessed firsthand the challenges and injustices that they faced. This personal connection fueled my passion for advocating for farmworker rights.

ML: What issues did you see your family face that made you want to advocate for farmworkers?

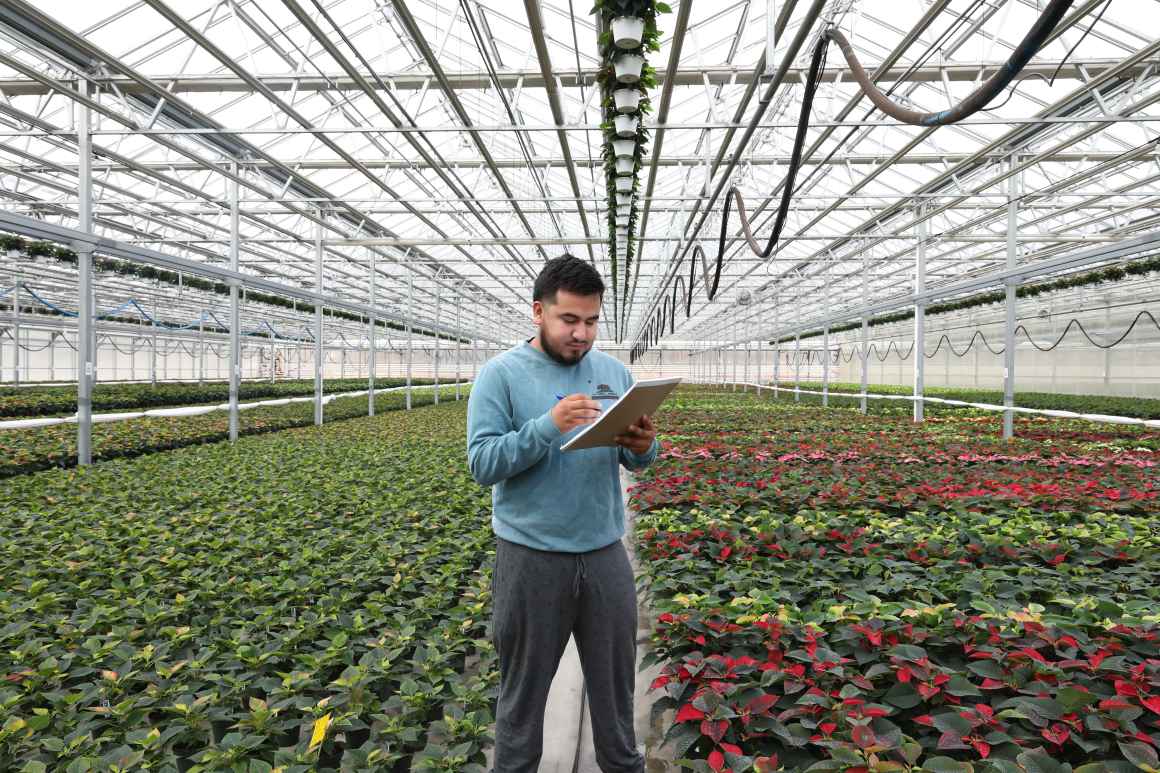

EAH: When my mom started working at a greenhouse when I was in middle school, they had the option to bring their kids during spring break – I was a mama's boy, so I always wanted to be with her anytime I could. One of the last times I went with her to work, I was in sixth grade, and that's when I had a wakeup call because I saw all the stuff that the workers are going through, and all the fear that came when the crew leader would show up. She would yell and tell them things like “they don't work,” and “they don't even know how to work."

When I talk about that being a wakeup call, it was because that was the first day I got angry about how my mom was being treated. My mom was always smiling, she was always this quiet, shy lady, and always lending her hand to help anybody. Right before the crew leader came in, I was helping my mom and the ladies she worked with, and we were all laughing while we worked. It was nice watching my mom kind of have this moment with her coworkers, just talking about life and enjoying each other’s company. But you could see the fear in their eyes when the crew leader came, and the ease in their eyes as soon as she left.

ML: It sounds like you found a lot of community there. And you went on to work there yourself, right?

EAH: Yeah, I think it's funny. I want to say I was a “nepo” baby. I went straight to being a grower, which was mainly putting chemicals on the plants. During the very busy season, I also worked outside planting or doing anything else that had to be done in the greenhouse. From about 13 to 18 years old, I was working in the fields picking crops as well, mainly tomatoes and peppers. And that was one of the hardest jobs that I've ever had because you had to move fast, and the boxes that you had to carry were very heavy.

ML: Did you ever get hurt, or did anyone else around you ever get hurt from that work?

EAH: Yeah, people would get hurt. When work was slow, we had to cut down tall grasses with machetes. I was afraid because I had never used a machete before in my life. I remember one of the guys got cut right next to his ankle.

I also remember the heat making people so tired and seeing it in my coworkers' faces. We picked everything by hand and it was hard to wear gloves because of the heat; I was sweating more and they made me feel uncomfortable. But I didn't realize the importance of wearing clothes; I wasn't aware of the pesticides and all the chemicals. As I got older, we got heat stress and pesticide trainings from outside agencies, but the information they were giving us was all stuff that wasn't actually being practiced at work.

During the trainings, nobody was allowed to ask any questions or to make any comments; the moment that you raised your hand to say something, the crew leaders would get up and say things like, “the company respects this,” “the company does that,” even though we know that it's not true.

It was hard for some people to speak up about concerns for fear of retaliation from their crew leaders. Either they wouldn't call them back for the next season or they would write them off and make up some excuse that they're not doing their work well.

ML: So, you’re now a farmworker organizer for CATA. How did you start your work there?

EAH: I started working on projects with them in South Jersey at the start of the pandemic in 2020. Farmworkers weren’t being recognized as essential workers, and my friends and I wanted to do something to honor them. We held a caravan for them in Vineland in May, which is where we could find the most workers, and had a lot of cars turn out. It was a good feeling because I've always wanted to do something like that and wanted to keep doing more for the community in general. We started doing food drives or food “dispensas” for people in the community. I was learning how to coordinate things and getting a sense of what it felt like to be a leader. Shortly after, Jessica, the General Coordinator at CATA, reached out about coming with her to one of their worker forums to learn more about the kind of outreach they do, and mentioned they had a job opening. I knew I wanted to apply.

ML: What do you do as a farmworker organizer?

EAH: Depending on the season, usually from April until October, we're doing farm work outreach. We visit farms in the evenings, usually after 5 p.m., because we're not allowed to visit during work hours. Workers ask questions, get training on things like pesticides, and we generally just check in with them so we know what's going on. We want to know if they are dealing with working conditions that are not okay with them, and to make sure they know what resources are available to them.

ML: Historically, farmworkers have been among some of New Jersey’s most marginalized residents which has made them especially vulnerable to unfair workplace treatment. Can you tell us about these sorts of challenges and how they impact people?

EAH: Growing up in a farmworker community, I saw the struggles that my family and my neighbors endured due to low wages, lack of political representation, and the vulnerability to exploitation. These challenges shaped my perspective and fueled my determination to advocate for change.

Farmworkers don’t earn a livable wage – it’s below the minimum wage that nearly all other workers earn in the State of New Jersey, and right now everything is going up in cost. People can't send as much money back home because they still must pay their bills here. And many have to waste money on a ride for a taxi to get to work because there is very little public transportation available in rural areas.

ML: In addition to your organizing work, you’re also a filmmaker. How does storytelling play a role in your work with CATA?

EAH: I knew I wanted to make movies and to tell the stories of people that live in my community, especially farmworkers in South Jersey, which isn’t really known except for like Atlantic City or the Jersey Shore. But there's just so many stories here, and I feel like we don't really hear about the history of immigrants here and the history of farmworkers.

I get most of my stories when I talk to people on my outreach visits. I feel like I have the gift of being a good listener, especially when I'm just listening to farmworkers’ stories. I thank God that I have a platform and a microphone where I can turn the volume up and give them the microphone to tell their own story. I'm obviously not their voice, but I can help give them the opportunity to find their voice.

All photos used with permission from Edgar Aquino-Huerta.