In 2019, the Woodbridge Police Department had several leads on a suspected shoplifter: the suspect left a Dunkin’ Donuts receipt on the floor of his abandoned rental car, his fingerprints on a glass door at the scene, and a water bottle in the trash with his DNA. He had even lost his sneaker during a police pursuit.

But because of misplaced reliance on face recognition technology, the police ignored these leads and instead rushed to arrest an innocent Black man, Nijeer Parks.

Any adequate investigation would have revealed that Mr. Parks had no more connection to the crime than you or any other reader of this blog post. Instead, Mr. Parks spent ten days in jail.

Because Mr. Parks decided to vindicate his rights in court, the public has been able to learn more about how the Woodbridge Police Department’s abject trust in face recognition led to this traumatic false arrest. The story illustrates why the ACLU-NJ has called for a total ban on face recognition technology: we cannot put our faith in a tool that is, in practice, a misidentification machine.

Face Recognition Technology Generates False Arrests and Undermines Police Investigations

The Woodbridge Police Department recovered a fake Tennessee driver’s license from the scene of the alleged shoplifting. The investigating officer took a picture of the fake license with his cellphone and emailed it to law enforcement partners in Rockland County, NY. The Rockland County investigator cropped the photograph, “altered the photo on the license a little to get the pixels clear,” and fed the fake license photo into face recognition technology. It returned just one possible match.

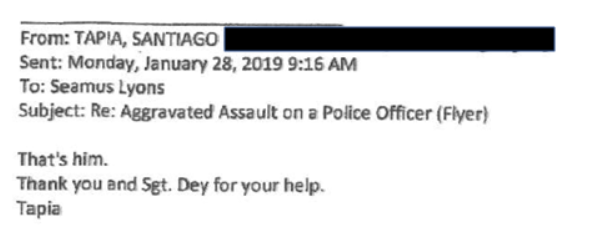

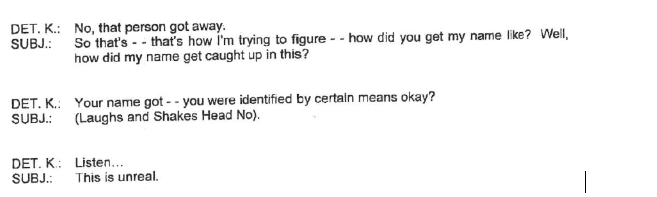

Within half an hour, the Woodbridge detective replied with a confident “that’s him.” Despite having other physical evidence that could have dispelled Mr. Parks as a suspect, the police proceeded to apply for an arrest warrant. The arresting detective wrote in the warrant that he had received a “high profile comparison” to the suspect photo, and declared with certainty that Nijeer Parks was the same person in the fake driver’s license photo. When Mr. Parks learned the police were looking for him, he went to the police station to clear his name. Instead, he was detained for ten days.

Narrator: It wasn’t him.

Every piece of this story highlights just how uniquely destructive face recognition technology can be.

First, the police officers relied on a dark, grainy, low-quality cellphone copy of an already low-quality fake license photo. But face recognition technology is only as good as the images that it analyzes, and images and photographs taken from crime scenes are frequently grainy, dark, and low-resolution.

But even if the photo is of the highest quality, face recognition technology still presents far too many dangers. Images of suspects usually capture them at awkward angles, not at the perfect “head-on” angle of the mugshots or drivers’ license photos they will be compared to. And those comparison photos might show the suspect at a younger age, with different facial hair, or wearing different jewelry. And these factors can become exacerbated for people of color if there is any inherent racial bias in the performance of the face recognition system.

Because of these factors, law enforcement use of face recognition, by necessity, can never identify a suspect with anything close to 100% certainty. At best, all we can say is that face recognition systems pick candidates who might be approximate lookalikes for a suspect in a photograph.

But Mr. Parks didn’t spend ten days in jail just because of face recognition’s technical limitations: he was arrested because the police placed uncritical faith in technology in spite of those limitations. This is what’s called automation bias: humans have a tendency to put undue trust or faith in the decisions of computers or machines. It can lead us to fail to seek out additional evidence. It can even override our own doubts that a candidate is not the actual suspect.

Excerpt from the police interrogation preceding Mr. Parks’ 10-day detention

Face Recognition Undermines Police Accountability

But we cannot absolve the police of responsibility just because of automation bias: the police department’s intentional choice to arrest an innocent man was the product of a critical failure to carry out any kind of proper investigation and, further, to heed multiple warnings that could have prevented the harm.

For example, the police should have known that regardless of their own confidence, face recognition candidates can only be treated as investigatory leads – meaning confirmation is needed before making an arrest. This is even stated prominently on the New Jersey State Police’s request form for face recognition assistance (emphasis in original): “Further investigation is needed to confirm a possible match through other investigative corroborated information and/or evidence. INVESTIGATIVE LEAD, NOT PROBABLE CAUSE TO MAKE AN ARREST.”

But the police undertook no such investigation. They ignored Mr. Parks’ alibi, disregarded the physical evidence, and misrepresented the truth: the investigating detective told the judge who signed the arrest warrant that after receiving a “high profile comparison” from face recognition, he had “compared the photo on the fraudulent Tennessee driver’s license to [Nijeer Parks’ known photo] and it is the same person.” But “high profile comparison” is a standard the officer made-up and doesn’t refer to anything specific. Despite the officers’ misstated confidence, Mr. Parks was not the real suspect.

Since then, there has been no accountability for what happened to Mr. Parks. And even if he is successful in his lawsuit, it won’t require the police department to change its practices.

Where Do We Go From Here?

We should not see this story as a one-off instance of malfeasance. What happened to Mr. Parks is the natural consequence of relying on face recognition in police investigations: every aspect of the technology and its role heightens the risk of misidentification, with little data to show its benefits.

Since Mr. Parks’ arrest in 2019, we’ve learned about at least six other innocent people across the country – five Black men and one Black woman – arrested solely because of a wrong face recognition match.

For these reasons, the ACLU-NJ called for a total ban on law enforcement use of face recognition technology.